Our study

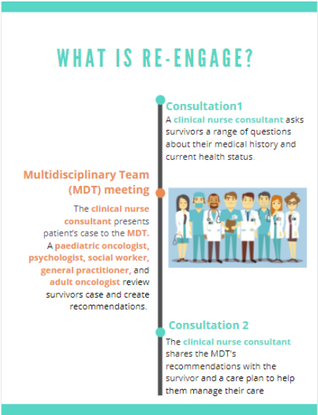

We recently published the findings of our pilot study in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. For the pilot study, we wanted to evaluate if Re-engage was feasible (i.e. can Re-engage be easily and conveniently completed by clinicians and survivors?) and acceptable (i.e. do survivors and healthcare practitioners like using the Re-engage intervention?).

We also wanted to collect early evidence of Re-engage’s impact on survivors’:

- confidence in managing their care and completing their survivorship recommendations

- engaging in recommended healthy behaviours (e.g. exercising, not smoking, eating healthily).

Our findings

Twenty-seven survivors completed the Re-engage pilot program. Using surveys, we asked participating survivors questions to understand their experience of Re-engage including feedback on what they liked and would change about the program. We found:

- 100% of survivors reported Re-engage as beneficial to them

- 92% of survivors reported Re-engage was easy to complete and to access

- 96% of survivors were happy with the amount and quality of information and help they received.

- Two survivors reported enjoying the remote delivery of Re-engage and that by doing Re-engage over-the-phone or online, it made it easier for them to coordinate their care.

- Survivors’ engagement in health behaviours (e.g. exercise) remained similar preintervention, postintervention, and at follow-up. However, they were more likely to have a regular GP who could help to encourage healthy behaviours beyond the program.

What’s next?

Our pilot study findings showed that Re-engage is acceptable and feasible, and early evidence suggests that Re-engage has the potential to empower survivors in coordinating their care and increasing their satisfaction with care. However, this study was only conducted with a small group of survivors and our next step is to run a much larger trial survivors in order to really understand Re-engage’s potential impact. In this new trial, we are also collecting data which will help us to implement this program into clinical practice after the trial ends.

If you would like to know more about Re-engage, including how to get involved, please click here.

The Re-engage pilot study was supported by Cancer Council New South Wales and The Kids' Cancer Project.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed