We know from existing research that a cancer diagnosis during adolescence or young adulthood can disrupt young people’s social development. Young people diagnosed with cancer may be less likely to graduate from higher education, or to stay employed, compared to healthy peers. Survivors may also miss school or work because of the impacts of cancer treatment. Or, they may struggle to keep up once they do return. While physical health problems, like fatigue, can be challenging, it can also be hard for young people to catch up on missed social life. Young people may find themselves socially isolated because of hospital appointments or not feeling well. Spending time away from friends, classmates or work colleagues can also lead to challenges keeping up with or enjoying social activities such as dating or activities with friends.

It is important to find a way to better evaluate young people’s social functioning concerns during and after cancer treatment. To do this, we wanted to first understand what social functioning means for these young people. How has it been defined in existing research? Second, we wanted to understand what tools have been used most often to evaluate social functioning in young people with cancer. Are these tools also evaluating what matters to these young people? And lastly, we wanted to identify what factors might affect young people’s social functioning during and after cancer treatment. Are there factors that researchers and clinicians could use to develop support services that prevent poor social functioning or promote good social functioning?

Our Review

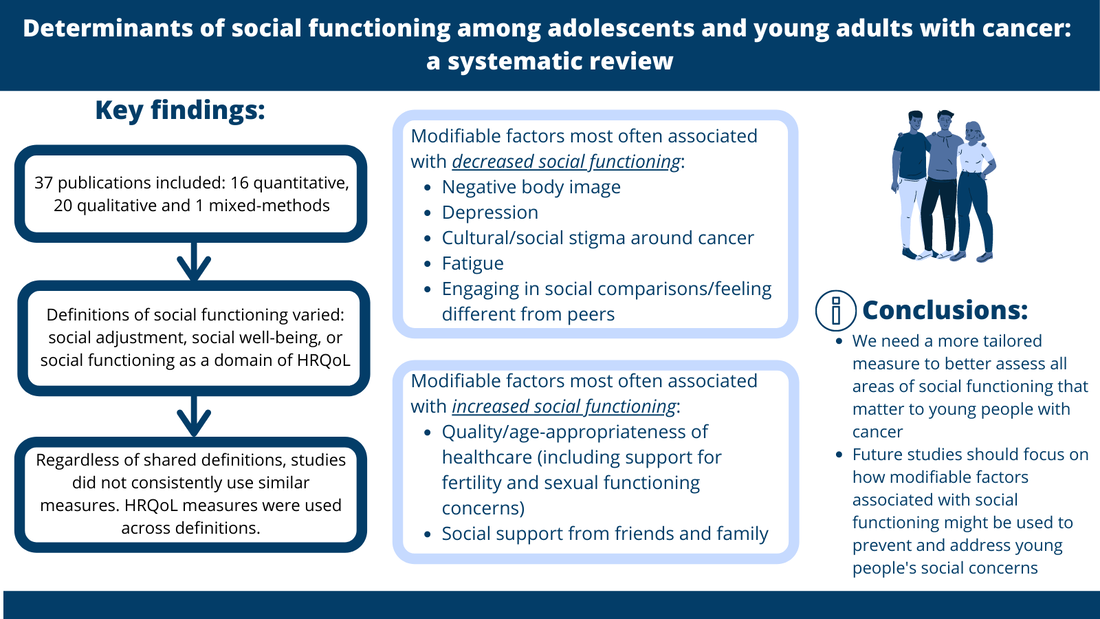

We reviewed 37 studies on social functioning among adolescents and young adults with cancer. We have recently published our findings in the journal Psycho-Oncology.

We found that 3 definitions were used to describe social functioning among adolescents and young adults with cancer:

- Social functioning as a domain of health-related quality of life: focused on limitations and difficulties with participation in social activities (19/37 studies)

- Social well-being: focused on one or areas in which cancer may affect young people’s social lives, such as education, employment, financial burden, interpersonal relationships and supportive care (16/37 studies)

- Social adjustment: focused on social skills, social behavior, peer acceptance and quality of friendships (2/37 studies)

Another important finding was how many different factors contribute to social functioning for young people with cancer. Negative body image, feeling different from peers/comparing oneself to peers, cultural/social stigma around cancer, depression, and fatigue are key contributors to poor social functioning among young people with cancer. On the other hand, having access to adequate social support from family and friends, as well as age-appropriate and high-quality healthcare that addresses young people’s fertility and sexual/intimate relationship concerns can help to protect and promote good social functioning for these young people.

To build on our findings, future research needs to determine the best tool(s) to use to measure young people’s social functioning during and after cancer treatment. To date, most studies have relied on measures of health-related quality of life, but these measures do not provide a clear picture of specific areas in which young people may be struggling. This makes it difficult to address social functioning concerns.

Lastly, researchers should collaborate with clinicians to develop support programs and interventions that address problems such as negative body image, feeling different from peers/comparing oneself to peers, cultural/social stigma around cancer, depression, or fatigue so that young people’s social functioning can be protected. On the other hand, to help make sure young people with cancer have access to social support and quality, age-appropriate care may help to promote good social functioning.

Conclusions

It is important to develop a specific measure of social functioning for young people with cancer that can provide both a detailed overview of their social functioning and identify specific areas of concern. It is also important that young people with cancer are given access and encouraged to participate in activities that protect and promote their social functioning. If researchers and clinicians can work together to accomplish both of these tasks, it might be possible to improve the long-term social outcomes of young people with cancer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed